Motions > Formations

Running a few plays out of many formations is a common offensive strategy in high school football, but I think motions are even more effective.

Over the last few years, I feel like the phrase, “one play many ways” has evolved into something along the lines of, “one play out of many formations.” I think that idea still has a lot of meat on the bone. The general idea behind it is:

We want to be able to get very efficient and proficient at very few plays. The more plays in the playbook, the less we get to practice each of them individually.

We can use formations to stress the defense and create a positive leverage to run those few plays while simultaneously presenting many looks for defensive coordinators to see on film later in the season.

Don’t get me wrong. I think this is still a very sound way to approach offense, but I think we can add to it.

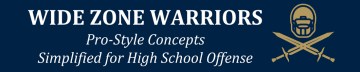

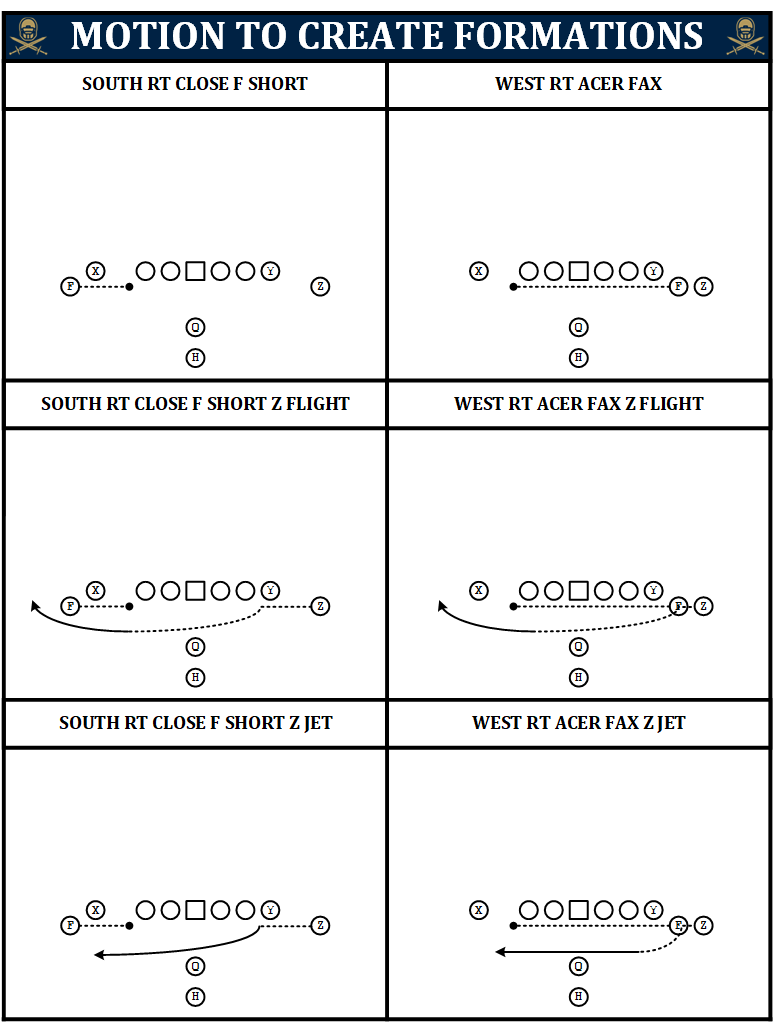

In watching a lot of Rams tape this season, I noticed a huge strategy from Sean McVay: the vast majority of their offense breaks the huddle into a very small number of formations, and he uses motions to create other formations. This diagram is a prime example of something I picked up on.

I haven’t broken down the entire season formationally, but the only times I can remember him actually lining up in the North formation, which is how the top two boxes finish (double tight, F off, X & Z tight splits), is when the backups are in. Instead of lining up in it, he has multiple ways of motioning to it.

So what does this do to a defense, and why is it better than running 150 formations in a season?

I like to get in the head of a defensive coordinator. Most of my mentoring came on that side of the ball, and a lot of how I view offense is through that lens. Most DCs that I know start their gameplanning process with formations and what plays are run from them. The prevailing thought among most OCs is that with a large amount of formations, we can “hide” some of our best plays. Against some DCs, that may be enough. The next step for DCs then is finding the tendencies. Tendencies are where the formation argument goes to die for me. If I want to run true Power, I have to have a fullback in position to secure a kick out. I can do anything I want with the other three eligibles, but if I have the common backfield tendency of having the HB offset to one side in the gun and a sniffer to the other, the DC might have a pretty good indication that Power is coming.

But what if that’s not how we break the huddle? What if the fullback starts wide and motions into the core? At that point, a DC likely doesn’t have time to call his Power-specific pressure. If he does, then it’s likely a one-word check that had to be worked on throughout the week, meaning less time spent in other areas of the gameplan.

Maybe they do make a check. What if we put another player in motion? Can we force the defense to check into and out of a pressure while keeping all 11 defenders on the same page, likely snapping while the second motion is on the move?

Ultimately, I think using motion to create formations can force defenses to play base. Again, thinking like a DC, formation recognition and tendencies do me no good when calling the play if the offense is motioning enough to where I know there’s a small chance the formation I’m seeing break the huddle is the same picture when the ball is snapped.

It sounds like a lot for players to know. How can we apply it? Paid subscribers will have access to how I’m evolving my offense using this theory, and this Monday night, we’ll also be hosting Georgetown College OC Caleb Corrill to learn how he protects his base concepts with shifts and motions as well!